What Does “Approved as to Form and Content” Really Mean in a Settlement Agreement? The California Supreme Court May Tell Us – Monster Energy v. Schechter.

The California Supreme Court has granted review in Monster Energy v. Schechter, an interesting case involving, in part, the meaning and binding-on-the-lawyer effect of the “Approved As to Form and Content” attorney signature line commonly found in California settlement agreements. The court’s eventual ruling in Monster Energy may lead to widespread reassessment of the inclusion of such signature lines in settlement agreements. Or it may not.

The facts of the case are pretty simple. The plaintiffs in an underlying case, represented by attorney Schechter, sued Monster Energy. That case settled. The plaintiffs and Monster Energy signed what appears to be a rather standard settlement agreement with broad release language and a confidentiality provision. The confidentiality provision stated that “Plaintiffs and their counsel agree that they will keep completely confidential all of the terms and conditions of this Settlement Agreement…” . The agreement was signed by the parties and included an “Approved as to Form and Content” line signed by the attorneys, including Schechter. Schechter was later interviewed by a reporter for a legal publication and, in the interview, made comments which Monster Energy alleged violated the confidentiality provision in the agreement.

Monster Energy sued Schechter and his law firm for breach of contract, breach of the implied covenant, unjust enrichment and promissory estoppel, asserting that Schechter was bound by, and had breached, the confidentiality provision of the settlement agreement. Schechter and his firm filed a SLAPP motion to strike under Code of Civil Procedure Section 425.16, asserting, in part, that Monster Energy could not establish the probability of prevailing under SLAPP Prong 2 because Schechter was not bound by the confidentiality provision. The trial court denied Schechter’s SLAPP motion as to the contract action but granted as to the other causes. As to the contract action, the trial court held that Monster Energy showed a probability of prevailing on the merits under SLAPP Prong 2 analysis because the settlement clearly contemplated counsel as being subject to the agreement because plaintiffs had the authority to execute the settlement agreement on behalf of their counsel and counsel signed the document. The trial court stated that Schechter’s “suggestion that he is not a party to the contract merely because he approved it as to form and content only is beyond reason.”

Schechter and the firm appealed. The Fourth District Court of Appeal in Monster Energy Co. v. Schechter (2018) 26 Cal App.5th 54 reversed and remanded, finding that the “Plaintiffs and their counsel agree…” language in the confidentiality provision was a “nullity” unless and until the attorneys consented to it and that the “Approved As to Form and Content” attorney signature line did not act as consent by the attorneys to the confidentiality provision. Thus, per the Fourth District opinion, Schechter was not bound by the confidentiality provision and could not have violated same with his interview comments.

Monster Energy petitioned the California Supreme Court for review. The court has granted review. One of two specific issues to be addressed in the review is:

When a settlement agreement contains confidentiality provisions that are explicitly binding on the parties and their attorneys and the attorneys sign the agreement under the legend “APPROVED AS TO FORM AND CONTENT,” have the attorneys consented to be bound by the confidentiality provisions?

What caught my attention about this case and the granting of review is that the “Approved as to Form and Content” signature line at issue is commonly used by, and signed by, by California attorneys settling cases. It is one of those things regularly included in settlement agreements because it has long been standard practice to do so and because it has been included in the form settlement agreements circulated around firms and amongst lawyers for years. Plus, the meaning of the “Approved as to Form and Content” attorney signature line has always seemed clear and self-evident. At least to me. It seemingly means only that the document has the attorney’s professional approval but does not reflect the attorney’s intent to be bound by the agreement. That is what the 4th DCA concluded in Monster Energy – the “Approved as to Form and Content” attorney signature line means only that the document has the “attorney’s professional thumb’s up”. Thus, it is quite interesting the Supreme Court wants to take a look at the meaning and binding-on-the-lawyer effect of this rather common attorney signature line in settlement agreements. This may very well turn out to be one of those cases where an Appellate or Supreme Court opinion causes California lawyers to reassess what has, for years and years, been standard practice.

Frankly, I have always shied away from “Approved as to Form and Content” lines in settlement agreements for a number of reasons. First, I have never really understood why I, as an attorney representing a party, need to acknowledge in writing that I have read and approved the form and content of an agreement that my client is signing. Inside my privileged relationship with my client, I have presumably made sure the client understands what he is signing to resolve a case. I have never really understood what the provision actually does. Further, most settlement agreements include integration clauses, and have a provision, or provisions, where the signing party affirmatively states she has read and understands the agreement, has had the opportunity to consult with an attorney concerning the terms and conditions of the agreement, and is freely entering into same. With such client representations, why is my approval as to form and content relevant or necessary? Further, adding the “Approved as to Form and Content” provision to an agreement, signed by counsel, would seemingly make it more difficult for the client to subsequently seek, through new counsel and where appropriate, to set aside the agreement for fraud, mistake, lack of consideration, …. etc. And, if the agreement were subsequently challenged, could my signature on an “Approved as to Form and Content” line make me a witness in such an action as to my understanding of the content and meaning of the agreement, as then-counsel for the signing party, and serve to waive my otherwise available work product privilege? To the detriment of my former client? I don’t know. It has always just to seemed to me that signing an “Approved as to Form and Content” provision could lead to a lot of unintended consequences and ethical problems if the settlement deal blew up and later ended in litigation. All for a provision usually included in the agreement not because it is a material, negotiated, term but because it has customarily been in such agreements.

Bottom line, signing the “Approved as to Form and Content” line has always seemed to me a weird thing to do, largely meaningless, and fraught with possible downstream unintended consequences. Others may perceive useful reasons for this provision – I really don’t. Perhaps a ruling in Monster Energy will serve to clarify the benefits and/or risks of such provisions, and lead to reassessment, one way or the other, of their use and inclusion in settlement agreements.

We shall see.

How I Work. I Know, Presumptuous, But…

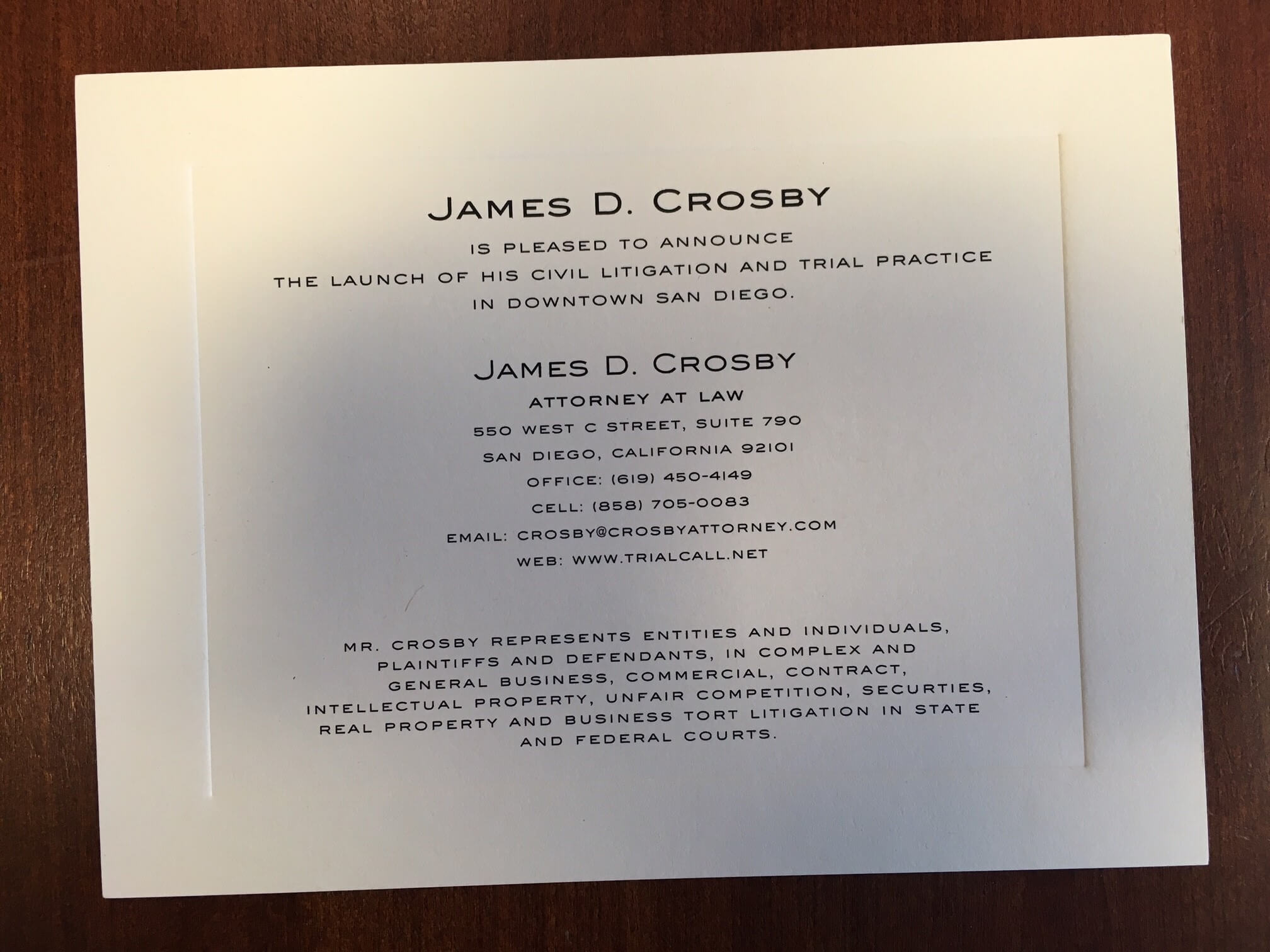

How I work! I know, presumptuous. Why would anybody care how I work? But, please read on. Recently, I have become interested in how people work, how they physically do their everyday work – how their desks/offices are set up, what devices/apps/software they use and why, how they communicate with clients/customers, what they don’t use and why, how they utilize tech to market, how they create content, etc., There are multitudes of devices, platforms, apps and software applications available for us to do our daily work in various settings. More and more pop up everyday. I want to be as efficient as possible in my work, and to utilize the newest devices and technologies to the extent they are cost-effective and match my skill set. Plus, I like machines, gadgets and apps! Sometimes old-school, tried and tested, stuff is best; most of the time, it isn’t, and we need to continually look at new ways to get our work done. So, I’m interested in how other lawyers work, how you work, and why. As a starting point, as a prompt to perhaps get a conversation started, this is how I work.

First, as background and for context, I have a solo business litigation/trial practice. On average, I try a couple of cases a year. Try them myself with necessary audio/video assistance. I usually have 12-15 open matters at any given time. Hourly work, with a few hourly/contingent blends and an occasional full contingency matter. I share office space with two prominent federal criminal defense lawyers and a smattering of other young criminal defense lawyers – truly, a suite of trial lawyers! I like my office mates very much – fine lawyers, good people. Large space, conference room for depositions and meetings. Shared receptionist who answers the phones. Large printer/scanner if needed. Location – downtown San Diego – two blocks from Superior Court and U.S. District Court. In the past, a flex-time legal assistant, now a full-time paralegal. I work with a fine contract attorney on a project basis. And, occasionally, a research project law clerk from USD. I think, a lean, efficient, and professional setting to work up and try cases. I like it.

Computers/Scanners:

Dell desktops and laptops (one for work, one for trial), fast processors and lots of RAM, each with a standard desktop printer and a Fujitsu ScanSnap iX500 scanner. The scanners are pricey ($500) but well worth. Great machines, efficient feeds, quick, work flawlessly. Large 36″ monitors.

Data Storage:

All my cases files are digital. We scan everything and maintain virtually no paper files. It took me some time to get to a true paperless office. The biggest jump was not creating and using electronic files, but, rather, getting rid of the corresponding paper. But, it doesn’t make much sense to go paperless, and still keep the paper. So, something paper comes in, we scan it, put the electronic version in its proper digital case file, and shred the paper. Small jobs we scan in-house. Large jobs, out to a vendor. This is getting to be less and less of an issue with electronic filing and service in almost every case. Physical client documents are likewise scanned and maintained electronically. To the extent we hold physical client documents, we, you guessed it, put them in bankers boxes in a secure location in the office.

My data is stored on Synology encrypted network-attached storage (NAS) devices. The NASs are in a secure location in my office and networked with the office computers. They contain multiple hard-drives which in turn maintain duplicate copies of all stored data. So, if a NAS hard-drive fails, we would just replace it, all data would be safe and duplicated again on the replaced hard-drive. All hard-drives on a NAS would have to fail at the same time to lose data. Additionally, each NAS is backed-up nightly to an encrypted external hard-drive. The NASs are easily expandable to much large capacities (up to 20TB) – just add larger and/or more hard drives.

My case and office files are located on one NAS. It’s all folder-based. Each case has a folder with sub folders for Pleadings, Discovery, etc., each containing the corresponding stuff, in .pdf format, maintained in chronological order. It’s just the digital equivalent of old-school paper case files with expanding folders and tabbed clips. Remember that?

Data/document productions from opponents and client data/documents are on a separate, much larger, NAS. This NAS is part of a recent eDiscovery upgrade to my office meant to ensure we can handle the eDiscovery data/document storage and production requirements of most any case.

For extra protection, all data on both NASs is backed up continuously on-line with Carbonite ($112/year). And, the back-up freak I am, I cycle a backup of all my data on an encrypted external hard drive to and from home on a weekly basis. I use Retrospect software to quickly duplicate and the update the data to the hard-drive. Needless to say, some very serious shit would have to happen for me to lose my data. And, with the exception of the cloud-based Carbonite backup, everything is in-house, encrypted, and password protected.

Offsite Access:

The NASs holding my case and firm data are accessible offsite through encrypted, multiple password-protected, VPNs incorporated into the Synology NAS software. They work great. I can work directly off my case files from my home desktop or anywhere with my laptop. Just need Wi-Fi, or cellular with the Personal Hotspot function on my iPhone. Except in instances of lousy Wi-Fi or cellular, there is little, if any, keystroke delay working through the VPN. This actually useable offsite file access is something that just a few years ago would have been cost-prohibitive for all but the largest of firms. Now, amazingly inexpensive.

Mobil Devices

iPhone, iPad, Dell laptop.

iPhone/iPad Apps:

I try to keep my iPhone relatively free of apps. Keep the distractions to a minimum. Two iPhone apps that I do like are Bear, a simple note-keeping app, and Adobe Scan, which allows me to scan and capture documents in .pdf format using the camera. And the audio-recording app described above. Spotify for music. Audible and Kindle for on-line reading material. (I do confess that in these fast-moving, interesting, often disturbing, times we live in, I have loaded and deleted Twitter from my phone dozens of times – what’s happening now (load) to too time-consuming (delete) to what’s happening now (load) to too time-consuming (delete) to…….. I think I have a problem in that regard). Honestly, I don’t use my iPad too much for work – some email and texting. I usually have my phone and laptop with me if I need to work. I do have the iPad Trial Director app, but haven’t used it yet.

Computer Software

Software not discussed or mentioned elsewhere in this piece. Adobe Acrobat DC ($30/mth). Sharefile ($20/mth) to move/share large files to/from/with clients and attorneys – works great. One of my office mates suggested dtSearch software ($100, I think). I am a big fan. It allows us to search, very rapidly, all my data in any networked location (like my NASs) using just words or phrases. Super fast and very effective.

Client Communications:

Office landline, iPhone, Outlook enterprise email across all devices, iPhone texts – all like most everybody else. And, yes, my clients have my cell number and are encouraged to call outside of office hours if need be. No worries on my end.

I also use MyCase software ($40/month) as a means to allow clients anytime access to case documents and calendars. The client gets a password-protected, encrypted, portal to whatever case documents we upload and a calendar of upcoming case events. Clients can access their portal anytime they wish. We plan to post pleadings, motions, court notices and orders, some discovery, and other assorted items to the client portals. Just rolling this out now to clients with a pretty favorable response. It’s take some staff time to upload stuff, but, the software is quite easy and I think giving clients anytime access to case materials and information is well worth the staff time. It’s interesting, I tried this software a number of years ago and, while it worked well, clients just didn’t use it. But, the world has changed rather dramatically since then and I think clients will now use and benefit from this online service. We will see!

Content Creation:

Word-processing – WordPerfect. I know, ridiculously old-school! But, I am very comfortable with WP. Word-processing is the simplest of functions and WP is simple software. I think it’s easier and much better-suited for legal work than Word. And the reveal code function is perfect. Plus, I have well-honed templates I have developed over the years in WordPerfect and I use them all the time. Most all content sent to clients is in .pdf format to maintain version control over working drafts. So, it doesn’t matter to them. At times, I will use Word, like when I am working on a stipulation or an order with opposing counsel. But, otherwise, its WP. I know, but there it is.

Perhaps the biggest change to my practice over the last decade is my increasing reliance on dictation software. I now dictate most everything – emails, memos, motions, orders, pleadings, letters (in those rare instances where I actually send a letter in the mail) – directly into the computer using Dragon Naturally-Speaking software. I use templates and dictate the substance and content into the template. I will edit, and clean things up, using a combination of keys and dictation. But, the more I type the less efficient I become. For me, speaking content is much faster than typing content. And, the recent versions of the Dragon software are simply extraordinary. Fast, remarkably accurate, and the more you use the software the better it gets. In some ways, for me, it is the perfect combination of old-school skills and new-school tech. I cut my teeth as a lawyer dictating most everything onto micro-cassettes for typing by staff. Yes, I am that “seasoned” an attorney. That dictation cadence I learned as a young lawyer works perfect with Dragon.

For a long period of time, I used a small Bluetooth headset, but begrudgingly. I just didn’t like wearing that thing. Now, I use a high-end desktop microphone – a Yeti USB microphone by Blue – sitting on my desk next to my monitor. It works great. I can literally walk around my office and dictate in a normal voice, the mic picks it up perfectly and my computer transcribes my content with remarkable accuracy. With a few verbal Dragon commands, I create, spell check, and send emails verbally, with few if any keystrokes.

On my laptop, a Dell XPS, I have found the resident microphone works remarkably well with Dragon and I have ditched the Bluetooth headset all together. I can simply speak at my laptop and, using Dragon, it creates my dictated content with great accuracy. In fact, large chunks of this piece were dictated by me sitting on the couch, the laptop on the coffee table, using Dragon and the mic resident on the laptop.

With my iPhone, I record stuff using a simple audio recording app and then email the recording to myself. Once back at the office, we can use Dragon to transcribe the audio recording. (I tried the Dragon Anywhere iPhone app and found it clunky and slow; my view, an audio recording for later computer transcription works much better.)

So, it all kind of circles back around, but with new tech and less overhead. In 1988, coming from a hearing, I would dictate an order or a notice of ruling into a micro-cassette and, back at the office, hand the cassette to my legal secretary to type up. In 2018, coming from a hearing, I will dictate an order or a notice of ruling into my phone and then email the audio to my office for my computer to transcribe. Amazing.

Legal Research:

Westlaw with California and San Diego County forms packets.

Trial Software

Trial Director

eDiscovery

As part of a recent eDiscovery upgrade to my office, we use or, more precisely, are learning to use Eclipse software with all data residing on a stand-alone NAS. So far, so good!

Time-Keeping/Billing/Financial:

For time-keeping and billing, I use TimeSlips, have for years. Bill monthly, invoices by email. I try to dictate my time entries directly into the program as I do the work, using Dragon. Pretty effective if I use the online eCenter software ($20/mth) component for time entry. The Timeslips program resident on my computers just doesn’t work well with Dragon making verbal time entry cumbersome. The online TimeSlips eCenter alternative works fine with the online time entries later synched to the computer TimeSlips database for billing. It’s ok, but, frankly, a bit cumbersome with a few required extra steps.

For that reason, I am considering moving my time-keeping and billing functions to MyCase which also hosts the client portals described above (all for $40/mth). It’s cloud-based and appears easy, quick, and intuitive. Plus, easy mobile time and cost entry on an MyCase iPhone app is a significant plus. There are some quirks in the billing component – for example, it can’t keep track of multiple case-specific trust fund deposits from a single client. Still assessing.

Finances – Quicken – 3 accounts – checking, trust, tax.

I have accepted credit card payments for years through my bank’s merchant services. But, it has gotten cost-prohibitive in light of newer attorney-specific payment services. I recently moved to LawPay. Works fine, simple. So far, so good.

How do you work?

That’s about it! How I work. I am always looking for new devices, software and apps, and new ways to do my work, in an ongoing effort to stay efficient and competitive in our fast-paced business.

So, how do you work?

The Discovery Rules.

I prefer getting documents and taking depositions as the principal means of discovery in most any case. If done right, the documents-then-depositions, with limited written discovery, approach is more cost-efficient and effective than any written discovery. Litigators, myself at times included, spend far too much time fighting over written discovery. We get locked in these little battles, these time-consuming discovery sideshows, driven by competitive instincts, by ego, by a desire to make the other side spend money, or even, at times, regretfully, by client animus towards the other side. These battles take on a life of their own, where just winning the battle, and not getting the discovery we think we want, becomes the all-consuming reason for the battle. This is not always the case, but if we are honest about it, we must admit that many written discovery disputes are more about the battle than they are about the discovery. Written discovery surely has its place in modern litigation and, at times, is well worth the fight to get it. But, a great deal of the time, it is not. With those comments as the backdrop, I offer up some suggested prescriptions for the ills that often infect our written discovery efforts – the Discovery Rules!

Rule 1:

Before proceeding with written discovery, simply and seriously consider whether it is worth the effort. It is a reasonable assumption with most any written discovery you propound will result in a larger discovery set coming back at you, lodged objections, lengthy meet and confer exchanges, threats of motions and sanctions, actual motions and sanctions, delayed trial dates, and increased costs to the client. Do you really need that written discovery? Does it align with your case theories? Can you get the information in a more candid response to a question at deposition? Basically – is the discovery response you seek really worth the hassle of getting it?

Rule 2:

As a corollary to Rule 1, never propound a written discovery request that you are not willing to enforce by motion. If the discovery is not important enough for you to enforce with a motion to compel, it is likely not important enough to propound in the first place. Why propound discovery that you are not willing to fight for? Do the cost-benefit analysis at the front-end rather than in the middle of the resulting discovery battle.

Rule 3:

Use requests for supplementation of an initial discovery set, rather than propounding successive sets of new discovery requests. Propound succinct, well-crafted, meaningful discovery requests at the outset, get responses, and then seek supplementation of those responses throughout the case. If you have to fight over that written discovery in the first instance, do so! But, once that battle is over, you should have a set of rock-solid written discovery requests which the court has passed upon and are not subject to further dispute. You can then seek supplementation of your opponent’s responses to those requests throughout the case without further dispute. If you have to fight over written discovery, fight once, and do so over meaningful, well-crafted, discovery that is necessary to your case or defense.

Rule 4:

Do not use form interrogatories for anything but the simplest of cases. They often, and most always in complicated cases, result in objections. And, in my view, rightfully so. Just the description of the “Incident” in anything but the simplest of cases is properly ripe for dispute.

Rule 5:

Do not include in your discovery requests definitions and instructions for how to respond. Most every discovery set I receive these days contains, at the outset, several pages of definitions and detailed instructions for how to respond. Quite often, these definitions and instructions require the responding party to do much more than the code requires and infuse privilege issues where none should exist. This is all completely unnecessary. The code says what it says as to the requirements for discovery responses. A simpler, more effective, approach is to simply propound the discovery – i.e, ask the question you want to ask – and expect back a response that comports with the code. Why fight over definitions and instructions that are not required by the code?

Rule 6:

As a corollary to Rule No. 1, but for the responding party, do not object to written discovery if you are not willing to defend your objection to the court under threat of sanction. If your opponent is following Rule No. 1, a motion is coming when you object. You thus need to determine whether the contemplated objection is really worth fighting over. Do the cost-benefit analysis at the front-end rather than after the battle has been joined by your opponent. If the objection isn’t worth the battle, why object? It’s a waste of time and money, and often undercuts the strength of your litigation position.

Rule 7:

Do not object to written discovery and then provide responses subject to, and without waiving, the raised objection. Either the discovery is objectionable or it isn’t. Does it really make sense to object to an interrogatory as vague and then answer it anyway? No. Also, following this rule requires you to undertake the honest analysis of whether a request is really objectionable or whether you are just throwing out objections to throw out objections.

Rule 8:

Meet and confer before responding to the discovery. If discovery is truly objectionable and you are willing to fight over your contemplated objection (see Rule 6), try to resolve the objection before responding. An email or, even better, a call to the other side identifying the issue and seeking resolution before you have to respond will serve to streamline resolution of legitimate disputes. If your opponent will amend and clean up an interrogatory before you have to respond, you will avoid a time-consuming discovery battle.

Rule 9:

Meet and confer face-to-face. If you are stuck in discovery battle, insist that the required meet and confer efforts are undertaken face-to-face. Let’s face it – most discovery issues are just not that complicated. They can be resolved, or properly teed up for resolution, through a face-to-face meeting (or a call if distance is a problem). The lengthy written meet and confer exchanges that characterize most discovery battles are not required by the code – the moving party in any discovery motion need only establish “a reasonable and good faith attempt at an informal resolution of each issue presented” C.C.P. Section 2016.040. Further, lengthy written meet and confer campaigns are usually not necessary and often just exercises in avoidance. Try this instead – sit down in a room, face-to-face, go over the objections, solve those you can solve, tee the rest up for resolution by motion, and confirm your agreements and disagreements in a simple writing. This approach will surely be more effective and cost-efficient than a lengthy letter-writing campaign. And, it is much easier for your opponent to take an unreasonable discovery position in a Friday afternoon email than it is for him to do so, over coffee, sitting across from you in a conference room.

Try these simple Discovery Rules in your next case. Get the discovery you actually need, avoid the discovery battles you don’t need, and streamline the discovery battles you must fight.

“Process of Trying A Case” Panel – Thanks!

Had the honor of sitting on a panel last night with Judges Bacal, Trentacosta and Wohlfeil of the San Diego Superior Court and Robert Francavilla of Casey Gerry for a SDCBA Civil Litigation Section program on the “Process of Trying A Case”. Part of yesterday’s “2018 Civil Lit Conference: Essentials for a Civil Litigator’s Toolbox”. I spoke on direct examination – that part of a trial that I, frankly, find the most difficult. Packed room. Great panel. Lots of fun. And I learned a few new things. Thanks to the SDCBA and the Civ Lit. Section for the opportunity!

2018 San Diego Super Lawyer for Business Litigation.

I am honored to be selected a 2018 San Diego Super Lawyer for Business Litigation!

Selected San Diego Business Journal Best of the Bar 2017

Honored to be selected a San Diego Business Journal Best of the Bar 2017.

Challenge the Opinion – Don’t Attack the Expert!

Challenging opinions and attacking experts is case-specific and can be quite nuanced. Particular cases can and do provide opportunities to effectively attack the credibility, expertise and even bias of an expert, even a smart, experienced, well-prepared one. But, there will be times when the opposing expert has done a fine job and reached a spot-on, fully-supportable, opinion, but based on incomplete facts and faulty presumptions provided by counsel. In those cases, it is always better to challenge the opinion and not attack the expert. See my new article in San Diego Lawyer. https://issuu.com/sdcba/docs/san_diego_lawyer_mar_apr_2017_issuu/26

Selected a 2017 San Diego Super Lawyer for Business Litigation

I am honored to be selected a 2017 San Diego Super Lawyer for Business Litigation!

Damn, I really wanted to do that cross!

I was scheduled to start a bench trial on Tuesday for a plaintiff in a property/easement dispute. Well-prepared, ready to go. Spent probably 8 hours over the weekend, alone in my office, no interruptions, tuning, re-tuning and fine-tuning the perfect cross-examination of the defendant. Going to call him right out of the gate, first witness, as an adverse witness under Evidence Code Section 776. It was going to be brutal, a thing of beauty.

Tuesday morning, in court, fully briefed, all set up, tech working, clients nervous but ready, witnesses lined up, ready to go – case settles! Good settlement, great result for client, fine conclusion to the case.

But, damn, I really wanted to do that cross!