Monday – arguing appeal of copyright case before the Ninth Circuit.

Today – preparing supplemental responses to form interrogatories.

Hmmm, wonder which is more fun?

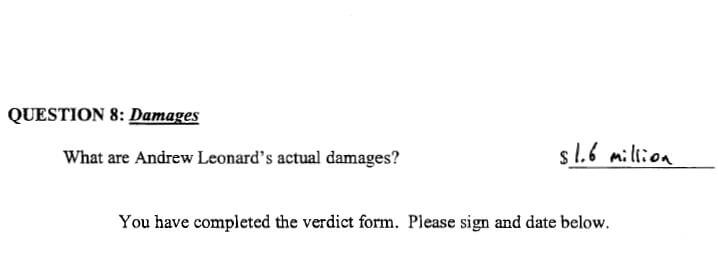

Sedlik’s Multiplier & Actual Damages for Copyright Infringement

Another fine piece from my partner, Doug Lytle!

Some days being a lawyer is extra engaging and challenging. In a good way!

Monday, it involved the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeal where I argued a copyright case. Of course, it’s on YouTube! What a world.

Anyone interested in seeing my five minutes or so of short-lived fame can go to 1:20:48 on the video. https://lnkd.in/b-F-Vhy

Hoping for a good result and another chance for my client in the District Court.

We will see.

Copyright Defense Win Reversed – Proving Authorization to Copy is Defendant’s Burden

This is a Trial Call guest post – an interesting piece on evidentiary burdens in copyright litigation from my partner, Doug Lytle. Doug discusses a recent Seventh Circuit copyright infringement case about making and distributing copies of a painting. The piece and the opinion identify some important pitfalls for copyright litigators, and offers some preventative guidance for those who make copies of or distribute the creative works of others. Thanks, Doug! Jim

California Supreme Court Affirms Use of Percentage Fee Awards in Class Action Cases Resulting in Recovery of Common Funds – Laffitte v. Robert Half International.

In a significant victory for consumers and plaintiffs class action attorneys, the California Supreme Court, in Laffitte v. Robert Half International, Case No. S222996, clarified existing case law and approved the use of percentage fee awards in class action cases resulting in preservation or recovery of a “common fund” for the benefit of class members.

Facts

The facts of the case were simple. In three related wage and class action lawsuits, the defendant agreed to settle for a gross settlement amount of $19M. Plaintiffs counsel sought a fee award of the 1/3 of the gross settlement, or $6,333,333.33. Nice fee! A class member objected to the fee request arguing it was excessive and not adequately supported. The trial court overruled the objection and awarded plaintiffs the requested 1/3 “contingent fee”. Interestingly, the trial court “double-checked” the reasonableness of the contingent fee award with standard lodestar-multiplier analysis.

The objecting class member appealed arguing the trial court’s award of an attorney fee calculated as a percentage of the settlement amount violated the Court’s holding in Serrano v. Priest (1977) 20 Cal.3d.25 (Serrano III) to the effect that every fee award must be calculated on the basis of time spent by the attorney or attorneys on the case. The Court of Appeal affirmed. The Supreme Court granted review on the single issue of whether Serrano III permits a trial court to calculate an attorney fee award from a class action common fund as a percentage of the fund, while using the lodestar-multiplier method as a cross-check of the selected percentage.

Holding

In a lengthy opinion discussing the history and anaytical underpinnings of percentage and lodestar methods of determining reasonable fees in class action litigation and California law post-Serrano III, the court upheld the use of percentage fee awards in class action cases resulting in recovery of common funds.

Whatever doubts may have been created by Serrano III, supra, 20 Cal.3d 25, or the Court of Appeal cases that followed, we clarify today that use of the percentage method to calculate a fee in a common fund case, where the award serves to spread the attorney fee among all the beneficiaries of the fund, does not in itself constitute an abuse of discretion. We join the overwhelming majority of federal and state courts in holding that when class action litigation establishes a monetary fund for the benefit of the class members, and the trial court in its equitable powers awards class counsel a fee out of that fund, the court may determine the amount of a reasonable fee by choosing an appropriate percentage of the fund created. The recognized advantages of the percentage method—including relative ease of calculation, alignment of incentives between counsel and the class, a better approximation of market conditions in a contingency case, and the encouragement it provides counsel to seek an early settlement and avoid unnecessarily prolonging the litigation (See pt. I, ante; Lealao, supra, 82 Cal.App.4th at pp. 48–49; Rawlings v. Prudential-Bache Properties, Inc., supra, 9 F.3d at p. 516)—convince us the percentage method is a valuable tool that should not be denied our trial courts.

The court specifically limited its holding to true common fund cases. It specifically did not address whether the percentage method may be applied when there is no conventional common fund out of which the award is to be made but only a “ ‘constructive common fund’ ” created by the defendant’s agreement to pay claims made by class members or when a settlement agreement establishes a fund but provides that portions not distributed in claims revert to the defendant or be distributed to a third party or the state, making the fund’s value to the class dependent on how many claims are made and allowed. These class action types and the availability of percentage fee awards in same are left for future consideration.

The Court also endorsed the use of traditional lodestar analysis to “double-check” or “cross-check” the reasonableness of the percentage fee award, but held that trial courts have discretion to forego same.

As to the incentives a lodestar cross-check might create for class counsel, we emphasize the lodestar calculation, when used in this manner, does not override the trial court’s primary determination of the fee as a percentage of the common fund and thus does not impose an absolute maximum or minimum on the potential fee award. If the multiplier calculated by means of a lodestar cross-check is extraordinarily high or low, the trial court should consider whether the percentage used should be adjusted so as to bring the imputed multiplier within a justifiable range, but the court is not necessarily required to make such an adjustment. Courts using the percentage method have generally weighed the time counsel spent on the case as an important factor in choosing a reasonable percentage to apply. (5 Newberg on Class Actions, supra, § 15:86, pp. 332–333; see, e.g., In re Thirteen Appeals Arising Out of San Juan Dupont Plaza Hotel Fire Litigation, supra, 56 F.3d at p. 307 [“even under the [percentage of fund] method, time records tend to illuminate the attorneys’ role in the creation of the fund, and, thus, inform the court’s inquiry into the reasonableness of a particular percentage.”].) A lodestar cross-check is simply a quantitative method for bringing a measure of the time spent by counsel into the trial court’s reasonableness determination; as such, it is not likely to radically alter the incentives created by a court’s use of the percentage method.

We therefore agree with the Court of Appeal below that “[t]he percentage of fund method survives in California class action cases, and the trial court did not abuse its discretion in using it, in part, to approve the fee request in this class action.” We hold further that trial courts have discretion to conduct a lodestar cross-check on a percentage fee, as the court did here; they also retain the discretion to forgo a lodestar cross-check and use other means to evaluate the reasonableness of a requested percentage fee.

Takeaways

Laffitte v. Robert Half International is a significant victory for plaintiffs class action attorneys and, in turn, for California consumers injured by unfair, improper, and/or illegal business and employment practices. Whether it will result in a significant uptick in California class action litigation remains to be seen. I suspect it will. The lure of large contingent fees will likely bring in more players.

Plaintiffs class action attorneys should not throw out their time slips or unload their timekeeping software. While percentage fees are available in common fund cases, the Court tacitly endorsed, though it did not mandate, use of a lodestar calculation to “double-check” the reasonableness of such percentage fee awards. In seeking percentage fee awards in class action common fund cases, plaintiffs would be well-served to evaluate and consider whether to offer a lodestar calculation “double-check” of the contingent fee sought. If the percentage fee and the lodestar “double-check” fee are within the same range, offer the lodestar as evidence of the reasonableness of the percentage fee.

But, if the percentage fee requested in a class action common fund case is far in excess of what the fee would be under a lodestar calculation, the likely best approach is not to offer a lodestar calculation and argue the court should “use other means to evaluate the reasonableness of a requested fee”. In such cases, plaintiffs counsel would be well-served to provide other evidence, including detailed declarations, adressing the risks and potential value of the subject litigation, the novelty and difficulty of the issues involved, the history and course of the litigation, the result obtained and benefit to class members, comparable percentage fee awards in comparable cases, and the time and resources expended on the case. Under such circumstances, expect defense counsel to urge the court to require further lodestar evidence of time spent and applicable rates and to argue for lodestar analysis as a check against an exorbitant, unreasonable contingent fee.

After Laffitte v. Robert Half International, the percentage fee award survives in California class action common fund litigation. Again, a nice win for the plaintiffs class action bar!

A Reasonable Limitation on the Vexatious Litigant Statute – John v. Superior Court, 63 Cal. 4th 91, By Leor Hafuta.

This is a guest Trial Call post by Leor Hafuta on John v. Superior Court, the recent California Supreme Court case addressing the vexatious litigant statute and its applicability in certain appeals. Leor is an incoming 3L at Loyola School of Law and a summer clerk at Henderson, Caverly, Pum & Charney, LLP.

A plaintiff declared a vexatious litigant cannot file a law suit in California without first seeking a court’s leave or obtaining legal counsel pursuant Cal. Civ. Proc. § 391.7 (“Statute”). The Statute, aimed at limiting misuse of the court system, allow courts to declare plaintiffs vexatious litigants if they have initiated five unsuccessful or unresolved lawsuits within the past seven years.

In John v. Superior Court, 63 Cal. 4th 91 (Cal. 2016), the California Supreme Court (“Supreme Court”) confronted the issue of whether the vexatious litigant Statute applies to defendants appealing a judgment against them. In the underlying case, the Defendant appealed an unlawful detainer judgment and an award of attorney’s fees against her. The court said it would entertain her appeals if she furnished security because she was a vexatious litigant. After the court dismissed her appeals for failure to furnish security, she petitioned the Second District Court of Appeal (“Court of Appeal”) to have her underlying appeal heard on its merits.

The Court of Appeals ruled that the vexatious litigant filing requirements did not apply to the defendant because she did not initiate the litigation. The plaintiff then petitioned the Supreme Court, arguing that a defendant who files an appeal is in the same position as a plaintiff filing new litigation. The Supreme Court disagreed with the plaintiff, holding that the Statute only applies to a plaintiff’s appeal, not the party who did not initiate the litigation.

Therefore, the Supreme Court affirmed the Court of Appeal’s decision and disapproved prior case law, which stated that the filing requirements apply to all vexatious litigant appellants.

Takeaways:

Ruling Otherwise Would be Equivalent to Saying Two Wrongs Make a Right: Overall, the case seems to place a necessary and logical limitation on the vexatious litigant Statute. The Statute provides an important mechanism for curbing an unrepresented plaintiff’s ability to file vexatious lawsuits (a wrong), especially when he or she is not subject to discipline from the state bar. However, if the Statute would apply when vexatious litigants appeal a case they did not initiate, the Supreme Court would essentially be punishing those vexatious litigants for their past actions rather than evaluating the appeal on its merits (also a wrong). Thus, the Supreme Court ruling was consistent with the intent of Statute to limit abuse of the courts.

A Vexatious Defendant on Appeal is in the Clear: If you ever find yourself filing suit against an unrepresented vexatious litigant, be aware that the Statute will not hinder that vexatious defendant from appealing a judgment in your favor. However, if the defendant frivolously appeals that judgement, you may be able to recover attorney’s fees under Cal. Civ. Proc. Section 907 or move for sanctions under Cal. Rules of Court, rule 8.276.

Caretaking Relationship Required for Elder Abuse Action Against Physicians – Winn v. Pioneer Medical Group, 63 Cal. 4th 148 (2016), by Rae Y. Chung.

This is a guest Trial Call post by Rae Y. Chung on Winn v. Pioneer Medical Group, the recent California Supreme Court case addressing Elder Abuse actions against physicians. Rae is an incoming 3L at UCLA School of Law and a summer clerk at Henderson, Caverly, Pum & Charney LLP.

In Winn v. Pioneer Medical Group, Inc., 63 Cal. 4th 148 (2016), the California Supreme Court addressed the requirements and limitations of the Elder Abuse Act under California Welfare & Institution Code Section 15657 as applied to actions against physicians. The Court in Winn interpreted Welf. & Inst. Code Section 15657 to require as a precondition to any action for neglect against a physician the existence of a certain caretaking relationship between the decedent elder and the defendant physician. This decision will make it substantially more difficult for personal representatives of decedents to successfully bring elder abuse actions against defendant physicians.

THE CASE

This case arose when the daughters of the decedent sued the defendant physicians for elder abuse along with their medical malpractice action. The decedent elder had sought medical care from the defendant physician from 2000 to 2009 on an outpatient basis. Throughout the years, the physicians noticed various symptoms of peripheral vascular disease and gangrene but the physicians never referred her to a specialist. In early 2009, the decedent was admitted to hospital, where her leg was amputated and she subsequently died from blood poisoning. The decedent’s daughters sued, asserting the physician’s failure to refer an elder patient to a specialist constituted neglect under the Elder Abuse Act.

THE RULING

The Court held that a caretaking or custodial relationship is a requirement for bringing suit for neglect under the Elder Abuse Act. The Court held that the focus of Welf. & Inst. Code Section 15657 is on the nature of the relationship between an elder and a defendant physician, not on the defendant physician’s professional standing.

SIGNIFICANCE

The Elder Abuse Act enhances recoverable damages for physical abuse or neglect of elders. Under California Code of Civil Procedure Section 377.34, the damages recoverable for a civil action brought by decedent’s personal representative are usually limited to pre-death penalties or punitive damages, but exclude pre-death pain, suffering or disfigurement. However, the Elder Abuse Act establishes heightened remedies by allowing the plaintiffs to recover damages for pre-death pain and suffering. The ruling in Winn precludes plaintiffs access to such enhanced damages in abuse actions against physicians under the Act unless they can plead and prove the existence of a “caretaking or custodial relationship”.

TAKEAWAYS

The Court’s decision in Winn was seemingly driven by policy considerations. The Elder Abuse Act establishes heightened remedies. Allowing plaintiffs to proceed against physicians under the Act and expose physicians to the enhanced remedies under the Act, in addition to potential professional negligence exposure and in the absence of any caretaking relationship requirement was seemingly viewed by the Court as overly harsh.

Thus, after Winn, it will be harder for plaintiffs to plead neglect under the Elder Abuse Act against physicians. Therefore, when proceeding against a physician for physical abuse or neglect under the Elder Abuse Act, plaintiffs will be required to plead and prove a substantial personal and caretaking relationship between the elder and the physician. In that regard, plaintiffs may consider the following issues:

- Whether the physician was seen on an outpatient or inpatient basis;

- Whether the physician was in a position to initiate or deprive an elder of medical care;

- Whether there was anyone other than the physician who controlled the scope of elder patient’s medical care; and

- The number of years the physician took care of the elder patient.

The California Supreme Court Addresses Application of the Hearsay Rule to Expert Testimony – People v. Sanchez, 2016 WL 3557001.

In a significant new decision, People v. Sanchez, 2016 WL 3557001, the California Supreme Court considered application of the hearsay rule to out-of-court statements offered as expert “basis” testimony. The case is essential reading for California trial attorneys. If you try cases – read it!

People V. Sanchez was a criminal case concerning gang-related crimes. At issue was admission of a prosecution expert’s description of the defendant’s past contacts with police offered as a basis for the expert’s opinion testimony. The expert had never met the defendant, had not been present during such past contacts with the police, and had no personal knowledge of same. The question posed was whether the expert’s description of the defendant’s past contacts with police was inadmissible hearsay or non-hearsay simply because it was offered as a basis for the expert’s opinion.

In a lengthy opinion, the Court in People v. Sanchez addressed in considerable detail application of the hearsay rule to expert testimony and established a bright line rule that where an expert relates to the jury case-specific out-of-statements and treats the content of those statements as true and accurate, those statements are hearsay. And, like all hearsay, such statements are inadmissible unless rendered admissible through applicable hearsay exception. In so ruling, the Court concluded that it “cannot logically be maintained” that such statements are not being offered for their truth. The Court explicitly disapproved its prior decisions concluding that an expert’s basis testimony is not offered for its truth, or that a limiting instruction, coupled with a trial court’s evaluation of the potential prejudicial impact of the evidence under Evidence Code section 352, sufficiently addresses hearsay concerns and, in the context of criminal cases, Confrontation Clause concerns.

While this is a criminal case which also addresses Confrontation Clause concerns in admission of such out-of-court statements in expert “basis” testimony, the Court’s discussion of the hearsay rule as it applies to expert testimony, and its bright line rule for application of the rule to case-specific out-of-statements offered as expert “basis” testimony, applies equally in the civil and criminal contexts.

People V. Sanchez provides a lengthy primer on the hearsay rule and application of the rule to expert testimony. The court addresses the difference between an expert’s testimony regarding her knowledge in her field of expertise, which is traditionally not barred by the hearsay rule, and testimony by an expert relating case-specific facts about which the expert has no personal knowledge, which has been traditionally precluded. The Court noted that this distinction between generally-accepted background information and the supplying of case-specific facts is customarily handled through the use of hypothetical questions.

Going back to the common law, this distinction between generally accepted background information and the supplying of case-specific facts is honored by the use of hypothetical questions. “Using this technique, other witnesses supplied admissible evidence of the facts, the attorney asked the expert witness to hypothetically assume the truth of those facts, and the expert testified to an opinion based on the assumed facts….” (Imwinkelried, The Gordian Knot of the Treatment of Secondhand Facts Under Federal Rule of Evidence 703 Governing the Admissibility of Expert Opinions: Another Conflict Between Logic and Law (2013) 3 U.Den.Crim. L.Rev. 1, 5; see Simons, Cal. Evidence Manual, supra, § 4:32, pp. 326–327; 2 Wigmore, Evidence (Chadbourn ed.1978) § 672, p. 933, italics omitted.) An examiner may ask an expert to assume a certain set of case-specific facts for which there is independent competent evidence, then ask the expert what conclusions the expert would draw from those assumed facts. If no competent evidence of a case-specific fact has been, or will be, admitted, the expert cannot be asked to assume it. The expert is permitted to give his opinion because the significance of certain facts may not be clear to a lay juror lacking the expert’s specialized knowledge and experience.

But, the Court stated that the line between an expert’s testimony as to general background information and case-specific fact testimony has become “blurred”, noting that case-specific facts in an expert’s testimony is often handled with an inquiry into reliability, admission of the case-specific facts, and a limiting instruction to the jury. Setting a new bright-line test, the Court held this “paradigm” is no longer tenable.

Accordingly, in support of his opinion, an expert is entitled to explain to the jury the “matter” upon which he relied, even if that matter would ordinarily be inadmissible. When that matter is hearsay, there is a question as to how much substantive detail may be given by the expert and how the jury may consider the evidence in evaluating the expert’s opinion. It has long been the rule that an expert may not “ ‘under the guise of reasons [for an opinion] bring before the jury incompetent hearsay evidence.’ ” (Coleman, supra, 38 Cal.3d at p. 92, 211 Cal.Rptr. 102, 695 P.2d 189.) Courts created a two-pronged approach to balancing “an expert’s need to consider extrajudicial matters, and a jury’s need for information sufficient to evaluate an expert opinion” so as not to “conflict with an accused’s interest in avoiding substantive use of unreliable hearsay.” (People v. Montiel (1993) 5 Cal.4th 877, 919, 21 Cal.Rptr.2d 705, 855 P.2d 1277 (Montiel ).) The Montiel court opined that “[m]ost often, hearsay problems will be cured by an instruction that matters admitted through an expert go only to the basis of his opinion and should not be considered for their truth. [Citation.] [¶] Sometimes a limiting instruction may not be enough. In such cases, Evidence Code section 352 authorizes the court to exclude from an expert’s testimony any hearsay matter whose irrelevance, unreliability, or potential for prejudice outweighs its proper probative value. [Citation.]” (Ibid., citing Coleman, supra, 38 Cal.3d at pp. 91–93, 211 Cal.Rptr. 102, 695 P.2d 189.) Thus, under this paradigm, there was no longer a need to carefully distinguish between an expert’s testimony regarding background information and case-specific facts. The inquiry instead turned on whether the jury could properly follow the court’s limiting instruction in light of the nature and amount of the out-of-court statements admitted. For the reasons discussed below, we conclude this paradigm is no longer tenable because an expert’s testimony regarding the basis for an opinion must be considered for its truth by the jury.

. . . . . . . . . . . .

Once we recognize that the jury must consider expert basis testimony for its truth in order to evaluate the expert’s opinion, hearsay and confrontation problems cannot be avoided by giving a limiting instruction that such testimony should not be considered for its truth. If an expert testifies to case-specific out-of-court statements to explain the bases for his opinion, those statements are necessarily considered by the jury for their truth, thus rendering them hearsay. Like any other hearsay evidence, it must be properly admitted through an applicable hearsay exception. Alternatively, the evidence can be admitted through an appropriate witness and the expert may assume its truth in a properly worded hypothetical question in the traditional manner.

In conclusion, the Court adopted the following rule:

When any expert relates to the jury case-specific out-of-court statements, and treats the content of those statements as true and accurate to support the expert’s opinion, the statements are hearsay. It cannot logically be maintained that the statements are not being admitted for their truth.

In a footnote following this rule statement, the Court explicitly disapproved its prior decisions concluding that an expert’s basis testimony is not offered for its truth or that a limiting instruction, coupled with a trial court’s evaluation of the potential prejudicial impact of the evidence under Evidence Code section 352, sufficiently addresses hearsay and, in the context of criminal cases, Confrontation Clause concerns.

Takeaways

People V. Sanchez seems less a recasting of the traditional distinction between an expert’s testimony regarding background information and his testimony as to case-specific facts than it is a reassessment and realignment of the rules to be applied by trial courts to maintain the sanctity of that distinction. It is stiffening of the rules to be applied by trial courts to maintain that traditional distinction.

In light of People v. Sanchez, trial courts, upon proper objection, will more closely police expert testimony to ensure case-specific facts presented by an expert as a basis for opinion are otherwise admissible under applicable hearsay exceptions. When opposing counsel objects to case-specific facts offered by an expert as hearsay, the trial court can no longer overrule that objection simply because those facts are a basis for the expert opinion testimony. Absent applicable hearsay exception, that objection will be sustained. This new rule gives well-prepared trial counsel a significant tool to challenge and preclude opposing party expert testimony which is not supported by admissible evidence.

Trial counsel presenting expert testimony will need to more closely scrutinize, and be well-prepared to address, the admissibility of case-specific facts relied upon by an expert, or risk having such testimony precluded or rendered ineffective in the eyes of the jury.

While People v. Sanchez does not directly concern the use of hypotheticals and assumed facts to elicit opinion testimony, the same rationales apply. Trial counsel may ask an expert to assume a certain set of case-specific facts for which there is independent competent evidence and then ask the expert what conclusions the expert would draw from those assumed facts. But, if no competent evidence of such case-specific facts has been, or will be, admitted, the expert cannot be asked to assume them.

The sloppiness with which many trial courts have policed the use of case-specific hearsay in expert testimony will be subject to more-strenuous appellate examination. Admission and a limiting instruction is no longer a viable option for the trial court. Trial counsel will be well-served to recognize this new reality and place greater attention on establishing an evidentiary basis for admission of case-specific facts which provide the basis for offered opinion testimony.

People v. Sanchez is an excellent primer on hearsay and application of the hearsay rule to expert testimony. Great language for in limine options and pocket briefs addressing hearsay issues at trial.

People v. Sanchez is required reading for California civil and criminal trial attorneys!

Trademark Refresher: What is a Family of Marks?

Another interesting IP post from my partner Doug Lytle – What is a “family of marks?”

California Shareholder Demanding to Inspect Corporate Records? You May Be Taking an Out of State Trip! – Innes v. Diablo Controls.

Under California Corporations Code Section 1601, a shareholder may, upon written demand, inspect the accounting books and records and minutes of a California corporation or a foreign corporation doing business in California. Shareholder inspection demands are regularly used by California shareholders, often times in connection with ongoing, or anticipated, shareholder or shareholder derivative litigation. In Innes v. Diablo Controls (2016), Case No. A145528, the First District Court of Appeal addressed where that inspection may take place, and it may not be in California!

In the Innes v. Diablo Controls case, Diablo Controls was a California corporation whose corporate books and records were kept in Illinois. The issue on appeal was whether, under Section 1601, the corporation had to produce the records for shareholder inspection in California or could do so in Illinois where they were maintained. Relying on what can only be characterized as dicta in a 2004 case, Jara v. Suprema Meat (2004) 121 Cal.App.4th 1238, and noting that the statute makes no provision that the requested records be brought in state, the Court held there was no obligation on the part of the corporation to bring the requested records to California for inspection. It need only make the records available for inspection “at the office where the records are kept”; in that case, Illinois.

So, under Innes v. Diablo Controls, if you are a shareholder making a section 1601 demand to inspect corporate records, and those records are “kept” by the corporation at a location outside of California, you could be buying an out-of-state plane ticket. The corporation has no obligation to produce the records for inspection at any location other than where they are “kept”. If that “kept” location is out-of-state, tough luck, you can be forced to go there to make the inspection.

Takeaways:

First, isn’t this a bit old school? Aren’t most business records maintained electronically these days, especially financial and accounting records? Aren’t most business records maintained in cloud storage? Where are such records “kept” within the meaning of section 1601? Isn’t focusing on where records are physically kept as the controlling factor for shareholder inspections a bit contrived and, frankly, silly in this day and age?

Second, this opinion could place substantial financial and logistical burdens on shareholders seeking basic corporate information. One could see California corporations seeking to avoid shareholder scrutiny setting up “corporate records” offices in far away, difficult to get to, locations. “We received your demand to inspect the company’s minute book and accounting records. Those records are kept in our “corporate records” office in Nome, Alaska. They will be made available there for your inspection on reasonable notice.”

The case does seem to leave a little wiggle room on this issue of the burden placed upon shareholders seeking to inspect corporate records. Appellants argued that under a “no required in-state inspection” interpretation of the statute a corporation could avoid a section 1601 inspection by simply sending the records far away. The Court addressed this concern as follows:

We agree that maintaining the records in a remote location to intentionally impede inspection would be contrary to the purpose of section 1601. However, there is no evidence of such obstruction here. To the contrary, Diablo Controls voluntarily and at its own expense transported many of the requested documents to California for appellants’ inspection. In addition, appellants have not alleged that requiring them to inspect the records in Illinois will preclude their ability to exercise their section 1601 inspection rights.

This language seems to leave open the possibility that a demanding shareholder could compel production of the corporate records in state by showing that the corporation maintains records in a remote location to intentionally impede section 1601 inspections or that remote production would preclude shareholders the ability to exercise their section 1601 inspection rights. But, these may be difficult, and expensive, burdens to meet to compel an in-state section 1601 inspection.

Third, the California legislature should amend section 1601 to require California corporations, and out-of-state corporations doing business in California, to maintain current accounting books and records and minutes in state for inspection by shareholders. The legislature should also amend the statute to allow, as an acceptable alternative to in state production of physical records for inspection, electronic production of corporate records requested under section 1601. Corporate rights should not trump shareholder rights when it comes to the inspection of basic corporate records. It should be made easier, and not harder, for California shareholders to inspect corporate records.

Fourth, I just don’t see this result holding up for long. It seems demonstrably unfair to generally less-powerful shareholders simply seeking to see corporate records. I suspect the California legislature will address this. It certainly should! And I suspect that subsequent decisions will open up broad judicial exceptions to a section 1601 “no required in-state inspection” rule.

But, for the time being, section 1601 inspections could require significant money and travel time to complete!